(From the Odgen Standard – July 4, 1914)

Memory of Trap Doors, Secret Elevators and Stove, Wherein Bodies of Women Were Burned, Haunted Man for Nineteen Years.

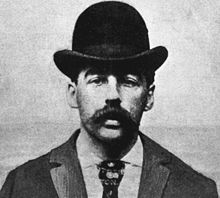

A few weeks ago word was sent over the telegraphic wires that Patrick Quinlan had killed himself in his home at Portland, Mich. The telegram did not cause much of a stir. Quinlan’s name had been forgotten. A new generation is reading the newspapers, which nineteen years ago carried stories day after day for months about the remarkable murder system of H .H. Holmes, with whose name the name of Quinlan was linked.

Quinlan proved his innocence. He showed that he was only an employee of H.H. Holmes, arch-murderer. He proved that he was Holmes’ janitor and caretaker of the Holmes Castle, 701 63rd St., Chicago, and nothing more. He admitted he had helped construct some of the secret trapdoors and had helped line some of the rooms with asbestos, which it is believed aided in deadening the sound of dying men, but Quinlan new nothing of the purpose of the traps he helped build, and had no part in the machinations of his chief.

Yet when the body of Quinlan was found lying in his room where he had taken poison, a note was found beside his body. The note said:

“I could not sleep.”

For nineteen years Quinlan could not sleep. At night he would wake with a start, and find himself covered with sweat, his friends say. He would call for help and when a light would be brought to his room or when the electric switch would be turned on he would recount how he was attacked while half asleep by strange hallucinations.

For nineteen years this man had been unable to sleep peacefully because of the awful experiences he endured during his employment by Holmes and during the period immediately after.

Holmes Castle was a three-story flat, looking more like an ordinary residence than like a castle. In that place it is believed four women, at least, were slain. It was the retreat of the man who also had killed men, women and children in Philadelphia, Toronto and Indianapolis.

The castle was built admirably for a murder shop. A dumbwaiter ran from the third floor to the basement and there were no connections with the dumbwaiter on the intervening floors. The conveyance was big enough to admit of a man riding upon it. On the top floor in one of the rooms was a gigantic stove. It was eight feet high and three feet in diameter. It was an ideal stove for the burning of a human body. A person could be thrown into the stove bodily and could be burned to nothing.

In the basement were quicklime vats. Bodies could be thrown in quicklime and consumed. The flagging in the basement could be torn up and bodies could be buried beneath the flags.

The trouble with the average slayer is that he does not know what to do with the body of his victim.

Finding of Body Starts Search

The finding of the body of the victim always starts the search for the slayer. If a man could dispose of the body he could slay on a wholesale plan and avoid detection. Holmes is believed to have built the castle with a view of hiding bodies of those he slew. He directed the work on the building. Quinlan was only an ordinary workman who did what he was told unhesitatingly. Quinlan never questioned the authority of the slayer. He never asked who the women were Holmes had visiting him. He never asked where they went when they disappeared. He was an ideal servant. Born in a small Michigan community, he went to Chicago to make his fortune. Chicago was about to have a world’s fair in commemoration of the discovery of America.

It was a good town to go to, thought Quinlan. An honest Irish young man, his only thought of making a living was by honest hard work. That is why he went to work for Holmes and worked so willingly and so faithfully. The other day when he drank the fatal potion he was middle-aged and broken in health. He looked as though he had been carried to the point of death by the ghosts of the slain women of the castle he helped to build.

It is said by some of his best friends that he often reproached himself for his part in the affair. He blamed himself for not suspecting Holmes and turning him up to the police. Yet he could not be blamed. Everything in Holmes Castle seemed to be right. There was no sign of murder there. Everything was quiet and still. The rooms were lined with asbestos and the dying victims never made a sound that reached the outside world. There at night in the dark house they met their death.

Some of them were asphyxiated, it is believed. Others were stabbed. Others were shot, according to the opinions of investigators. No one knows. Holmes knew and the victims perhaps could tell harrowing tales if they could talk, but they are gone and Holmes has been hung for his crimes, so in this world no one ever will know.

How many crimes Holmes devised no one can tell. The first thing to attract the attention of the world was the sudden, horrible death of B. D. Pietzel, a chemist, in Philadelphia. He died in such a manner that it seemed he had been making chemical experiments and had met with an accident when his chemicals exploded. Holmes, whose right name was Herman W. Mudgett, telegraphed to St. Louis to the home of Mrs. Pietzel and told her to come to Philadelphia and identify the body.

It is alleged that Holmes met Mrs. Pietzel and informed her the body was not that of her husband but that her husband had his life insured for $10,000.

“He’s safe in Canada,” Holmes told Mrs. Pietzel. “He had me frame up his body. It is so badly mangled by the explosion that no one can ever recognize it. You identify it and we’ll get the insurance. Your husband said for me to give you half and bring the other half to him.”

Mrs. Pietzel later confessed that she identified the body without believing it was that of her husband. She thought it was a big swindle game on the part of her husband and she entered into it readily. She brought her three children, Alice, Nellie and Howard with her. Alice was 15 years old. Holmes separated her room from her children and took them to Toronto, Canada.

Later the bodies of Alice and Nelly were found in the cellar of the building Holmes had occupied at Toronto.

Tip from Crook Revealed Holmes

Marlin Hedgepeth is the man who first directed attention to Holmes. Holmes was conducting the drugstore in St. Louis when he was arrested on a minor charge and placed in jail. There he met Marion Hedgepeth, noted as an out and out criminal. Holmes asked Hedgepeth to tell him the name of some St. Louis lawyer who could give him assistance in putting over an insurance swindle. Hedgepeth said he gave him the name. In return Hedgepeth was to get $500. This swindle was consummated. That is Pietzel was killed in Philadelphia in order to collect the insurance, but Hedgpeth got no money.

Then Hedgepath notified Chief of Police Harrigan of St. Louis that he had “the biggest insurance swindle case the police ever had to deal with anywhere, anytime in the world.”

He sent that message to Harrigan October 9, 1894. Pietzel had died September 3, 1894. That failure to deal squarely with Hedgepeth is doubtless what cost Holmes his liberty and life and checked his long career of crime. Police at once set out to hunt for him. The Philadelphia death of Pietzel had caused them some wonder, but the word from Hedgepeth made them doubly sure of crime. They trailed Holmes to Toronto, where the bodies of Alice and Nellie Pietzel were found. Later they found the body of Howard in Indianapolis and identified it as that of Howard, because of some peculiar playthings he had. His body had been burned in the stove and the bones alone were left intact.

Holmes was found in Boston and arrested. He was going under the name of Howard there. He was arrested July 14, 1895.

Mrs. Pietzel told her part in the affair and tried to atone by fighting for the conviction of the man who had made her a widow and slain three of her beautiful children.

In Chicago the record of Holmes was looked up. When he was under arrest in Philadelphia awaiting trial for the death of Pietzel word came from all parts of United States that Holmes, or a man answering his description, had taken women from their town and the unfortunates had never been heard from. From Fort Worth came the information that Miss Minnie Williams and her sister, Anna, had been led away by Holmes several years before and no one had ever heard of them. It was found that Miss Minnie Williams had entered Holmes Castle under the supposition that she was to be the wife of the arch-slayer. She sent to Fort Worth for her sister, Anna, to be a bridesmaid at the wedding.

The sisters had $60,000 worth of property in Fort Worth. They were induced to borrow heavily on the property and that is the last anyone heard of them. Minnie, the bride-elect, died before the wedding in Holmes Castle. Anna the bridesmaid-to-be, also died without ever having a chance to wear her bridal clothes. What happened to the bodies no one knows for certain. In the flue of the chimney, which led from the big stove on the top floor, hair was found. It is believed that the hair was that of the sisters as it corresponded to their hair. The theory was advanced at the time that the sisters were thrown into the stove and burned. The suction of the flue carried the hair up in the flue, where it remained as needed evidence against Holmes.

From Davenport, Iowa came another story of disappearance and Holmes name was linked with that too. Mrs. Julia Connor and her daughter where the missing ones.

Beautiful Woman and Daughter Lost

For more than three years prior to 1895, Mrs. Julia L Connor and her daughter, Pearl, had been missing from their friends in Iowa. Mrs. Connor had gone to Chicago with her husband and daughter to work in the drugstore conducted by Holmes. The drugstore failed and Holmes gave the property to Connor. Mrs. Connor was so taken with his generosity that she ceased to love her husband. She returned to Davenport and Connor obtained a divorce.

Then she returned to Chicago, ostensibly to open the boarding house in Chicago or the suburbs. She and her daughter never were heard of again. When Holmes was arrested in Philadelphia, relatives of Julia Connor claimed he killed her.

Many bones were found around Holmes Castle. He explained they were beef bones. He explained that the flat had been used as a restaurant during the World’s Fair at Chicago and that much meat was used there. He explained that the huge dumbwaiter was used to convey food. He explained that the asbestos was to make the house fireproof and to keep out cold.

He had an excuse for everything. He admitted he was crooked. He explained that he went to Toronto to smuggle furs into the United States. He admitted knowing all the women he was accused of murdering. He admitted knowingPietzel. He denied killing any of them. Damaging evidence against him were buttons of the women he was charged with killing, which were found in his castle.

But the defense of Holmes netted him nothing. He swung from the gallows for his crimes.

Though Holmes paid for his misdeeds with death, Quinlan suffered much more than he. He was arrested with Holmes but freed. When he went back to his Michigan home he found himself the center of eyes. Everywhere he went he was stared at or else he felt he was stared at. While the rest of the world forgot Holmes, the little town where he lived always rehearsed the story.

No wonder the honest Irish janitor finally picked up a piece of paper and wrote, “I could not sleep.” No wonder that after writing that simple line which told the story of nineteen years of suffering and horror, that he took poison and ended it all.

Holmes Murder Castle

Holmes Murder Castle